In August 2022, US defence officials confirmed open-source intelligence (OSINT) sightings that the Ukrainian Air Force had been using AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missiles (HARM), launched from Ukrainian aircraft. The confirmation raised questions regarding the compatibility between Western munitions and Ukraine’s ex-Soviet aircraft fleet. The news also added to the ongoing discussion regarding the air domain in Ukraine, in particular the conduct of SEAD/DEAD (suppression-of-air-defense/destruction-of-air-defense) missions by both sides. Despite possessing a substantial qualitative and quantitative advantage on paper, the Russian Air Force (VKS) has been unable to establish air dominance in Ukraine. This is likely related to the Russians’ inability to conduct effective SEAD/ DEAD operations, linked to factors including the high mobility of Ukrainian air defences (including S-300, SA-11s and SA-8 units), effective intelligence, poor Russian training and the supply of capable Western man-portable air-defence systems (MANPADS). Ukrainian use of AGM-88 munitions underscores this Russian failure, demonstrating that the Ukrainian Air Force is still capable of contesting the air space in Ukraine and limiting Russian aviation.

Anatomy of SAM systems

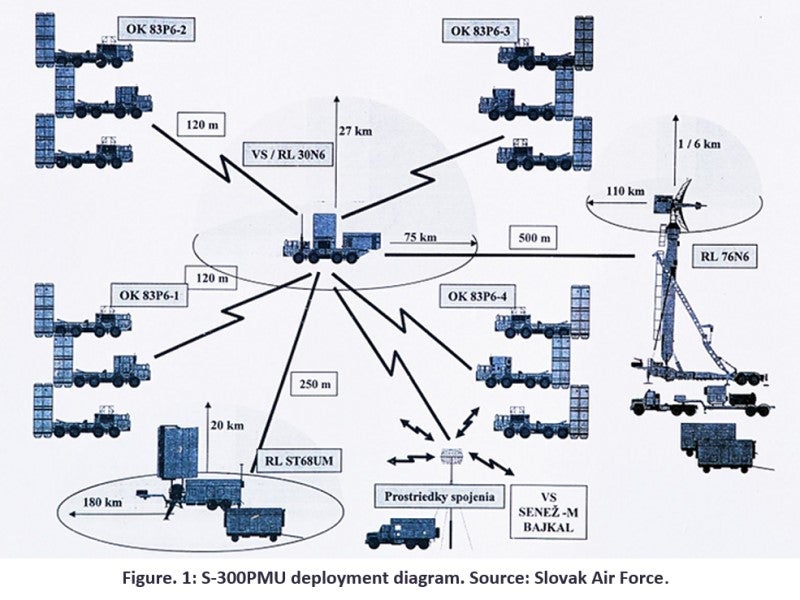

In order to understand the use of HARM missiles in Ukraine, and the topic of SEAD/DEAD more generally, it is first necessary to understand the anatomy of anti-air capabilities on both sides in Ukraine. Broadly speaking, surface-to-air missile (Sam) systems operate by detecting incoming aerial threats using radar and then engaging these threats, most commonly with missiles. It must be understood that the longest-range SAM systems, such as the S-300, are not individual units. They are instead a complex of systems, each performing a specific role. For example, Figure 1 shows the constituent units of an S-300PMU (SA-10B Grumble). The chart shows that within each S-300 unit, there are four 83P6 fire units (OK 83P6-1, OK 83P6-2, OK 83P6-3, OK 83P6-4). These fire units are each comprised of a 5P85SE TEL (transporter erector launcher) and two 5P85DE TELs. They are all linked to three separate radar units; a 30N6-1 Flap Lid B engagement radar, and ST-68UM Tin Shield and 76N6 Clam Shell acquisition radars, located within 120m, 250m and 500m of the fire units respectively. Broadly, acquisition radars are used to initially detect incoming threats whilst the engagement radar tracks the threat and provides the data necessary for the launchers to interdict the threat. Finally, these systems are connected to an automated command post (ADCP), in this case, a 5S99-M Senezh-M or 5N37/73N6 Baikal, which coordinates and distributes data from other units and generally controls the complex. There is great variety among S-300 systems regarding the exact specifications of the constituent units, and not all SAM units are comprised in the same way. For example, the Tor low-altitude, short-range SAM system uses a TLAR (transporter, launcher, and radar) design, in which the radar and launcher are incorporated onto a single-tracked vehicle bed. The trade-off with this design is the detection and engagement ranges are dramatically reduced.

This is relevant in Ukraine for the use of AGM-88 HARMs, as they function by detecting and homing in on the sources of active radar emissions. The missile can be deployed in several launch modes, with the modes being differentiated by whether the missile has a specified target prior to launch, and the range at which this target is engaged. When used in dedicated SEAD aircraft, such as the US Wild Weasel F-16, HARMSs are typically launched in pre-brief mode. In this mode, aircraft sensors detect a target and download this data to the missile prior to launch. This mode grants the greatest standoff range for attacks on emitters of a known type and location, and is therefore the best option for dedicated SEAD/DEAD aircraft. In other launch modes, the missile’s on-board sensors, rather than the aircraft’s, can acquire a target before launch or be launched defensively and prosecute targets acquired after launch at close range. When deployed against a SAM system, for instance an S-300, the aircraft or missile will detect active radar emissions from radar units and home in on the source of these emissions, the radar units. Whilst critical units such as the ACDP or TELs remain unscathed, the system as a whole has been crippled as the SAM system will have a degraded capability to detect incoming threats, a prerequisite for interdiction.

Use of HARMs in Ukraine

Whilst physical adaptions would be needed to allow HARM missiles to be launched from Soviet aircraft hardpoint pylons, this is not the most challenging factor. For the missile to be used effectively, a data interface must be established between the pilot and munition, allowing information regarding potential targets’ location and characteristics to be passed. For this to be achieved, significant modifications to Ukrainian aircraft would be required. NATO does however have experience in modifying Soviet-era aircraft to increase their compatibility with Nato equipment. For instance, both Poland and Slovakia have modernised their MiG-29s to better align with Nato standards. Furthermore, Ukraine has also demonstrated its ability to adapt and use Western weapons in ways for which they were not designed. For instance, Brimstone missiles designed for launch from aircraft and rotorcraft have been observed being launched from modified trucks.

Furthermore, it is unclear in what role the Ukrainian Air Force has been using the HARMs supplied by the US. Notwithstanding strikes conducted by expensive stealth unicorn platforms, such as the B-2 bomber, the US and the West typically rely upon complex operations involving a range of aircraft, including dedicated SEAD/DEAD aircraft (equipped with anti-radiation missiles), EW aircraft and conventional fighters. The operations work tactically by threatening key targets, compelling enemy SAM units to reveal themselves and engage the incurring aircraft, allowing them to be subsequently targeted by the dedicated SEAD/DEAD aircraft. These operations are difficult, risky and problematic even for well-trained pilots in professional Western air forces. The operations are hazardous as they rely upon drawing detection from enemy units, with there being a short window between enemy SAM units emitting radar pings, and the launch of SAM missiles. Furthermore, in the congested environment with many aircraft of multiple types in formation, the possibility for friendly fire incidents is high. Indeed, during Desert Storm a friendly fire incident is thought to have occurred in which a HARM missile fired from an F-4G locked onto the tail radar of a friendly B-52, resulting in heavy damage. The incident underscores a key limitation of the HARM missile, and SEAD/DEAD missions more generally; it is highly challenging to stimulate an enemy SAM response whilst simultaneously diverting enemy radars without putting friendly aircraft at risk. Furthermore, due to the requirement to first stimulate an enemy response, the ability to reactively target SAM threats is limited.

It is unlikely that the Ukrainian Air Force is conducting large SEAD/DEAD operations of this kind, seeking to entirely eliminate Russian anti-air capabilities in the region. Firstly, a major success for Ukraine thus far in the war has been its ability to preserve a substantial portion of its fleet despite the VKS’s numerical advantage. Ukrainian commanders would likely not be willing to put their remaining aircraft at risk to conduct SEAD/DEAD operations. Preserving a force-in-being allows Ukraine to continue to contest the air space and deny Russia air dominance. Furthermore, with Ukraine possessing a fleet of solely Soviet-era aircraft, Ukrainian pilots would not have the requisite familiarity with HARM missiles to effectively carry out such operations. Instead, it could be argued that these munitions could be effective at suppressing Russian anti-air for short periods in small areas, allowing for localised Ukrainian air support at low altitudes in aid of ground offences. The mere knowledge that HARM missiles are present in the region could be enough to drive Russian commanders to not reveal their SAM units, and so allow Ukraine limited use of the airspace.

Russian SEAD/DEAD operations in Ukraine

In the initial phases of the war, Russian electronic warfare techniques were successful in suppressing Ukrainian air defences, allowing Russian fast jets and rotorcraft a degree of freedom in Ukrainian airspace. An example of this is the airborne assault on Hostomel Airport, which used Russian Mi-8s, Ka-52s, Su-25s and l-76s (which were unable to land due to a Ukrainian counterattack). The Russian VKS also carried out strikes against SAM sites, eliminating static SA-3 SAMs and a limited number of S-300PS/PT units. However, conventional VKS fixed-wing strikes have been unable to eliminate mobile SAM units, such as the SA-11 Buk system, which uses highly mobile TELAR (transport, erect, launch, and radar) vehicles, SA-8s, S-300PS/PTs, and S-300Vs. The preservation of S-300 variants along with the SA-8s and SA-11s, have combined to make flying at high and medium altitudes prohibitively dangerous for Russian pilots. Since the initial phases of the war, Russian air patrols have been conducting low-altitude DEAD missions, flying close to Ukrainian airspace prompting Ukrainian SAM units to turn on their radars, and then engaging with Kh-31P and Kh-58 ARMs. These are Russian anti-radiation missiles roughly analogous to the HARMs now used by Ukraine. This operation has reportedly had mixed results in terms of Ukrainian units eliminated.

OSINT has indicated that Russian commanders are instead turning to unconventional techniques to conduct SEAD/ DEAD missions, using unmanned platforms, loitering munitions, artillery strikes and cruise missiles to eliminate Ukrainian SAM systems without using anti-radiation techniques. It has been reported that formations of Orlan-10 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which are outfitted with electronic warfare capabilities, have been used to penetrate Ukrainian air space. This then prompts Ukrainian medium-altitude SAMs to turn on their radars, allowing them to be located and suppressed for long enough to relay their coordinates for artillery and missile strikes. Additionally, footage has been circulating in Russian mil-blogger channels of a similar technique being used whereby Russian tactical drones, such as the Orlan-10, have sought out and suppressed Ukrainian TELAR SAM systems, and then guided loitering munitions, such as the ZALA Lancet or HESA Shahed-136 to the area. The loitering munition can then be guided manually to the target. Going forward, it could be argued that this method of DEAD operations raises problems for military planners and could change the way SEAD/DEAD operations are formulated. It is essential for modern warfare that the airspace is at the very least contested, as it is in Ukraine. However, through the use of drones, Russian commanders have found a cost-effective means of using cheap unmanned platforms to effectively target expensive and strategically vital SAM systems, and force Ukrainian commanders to move SAM units further from the frontlines.